Historians sometimes speak of a concept called ‘teleology’ and dangers that can come from it. It is reading of historical events as being small parts that largely only have meaning and interest to us in how they contribute to a much bigger historical story – often one that is well-known and indisputable. The concept comes with the risk that the parts can be seen as inevitable and that there’s a destiny in the making.

With reference to World War II, we know the outcome already – spoiler: the Axis powers of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan do not win! It can lead us to assume that the nearer events approached Victory in Europe on 8th May 1945, that there was an inevitability that the war would go in the favour of the Allies; the Nazis suffering more losses than victories on the battlefield, including the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaigns on British towns and cities.

When the tenth raid on York occurred in the early hours of Thursday 24th September 1942, the outcome of the war was very much unknown. Many British citizens were still fearful for the future. The tenth raid on York came a point in the war where the British Army was still to win a meaningful military campaign. (They would not do so until the Second Battle of El Alamein in November 1942). By comparison, the day before the tenth bombing raid on York had witnessed the German Wehrmacht fight their way to the centre of Stalingrad against Soviet forces. Whilst the fate of a near 1 million of those German troops would be sealed just over four months later as death or captivity, for Allied military intelligence it was yet another major victory for the Nazi military machine. There was no clear end to the war in sight, at least not one offering a good outcome for the Allies.

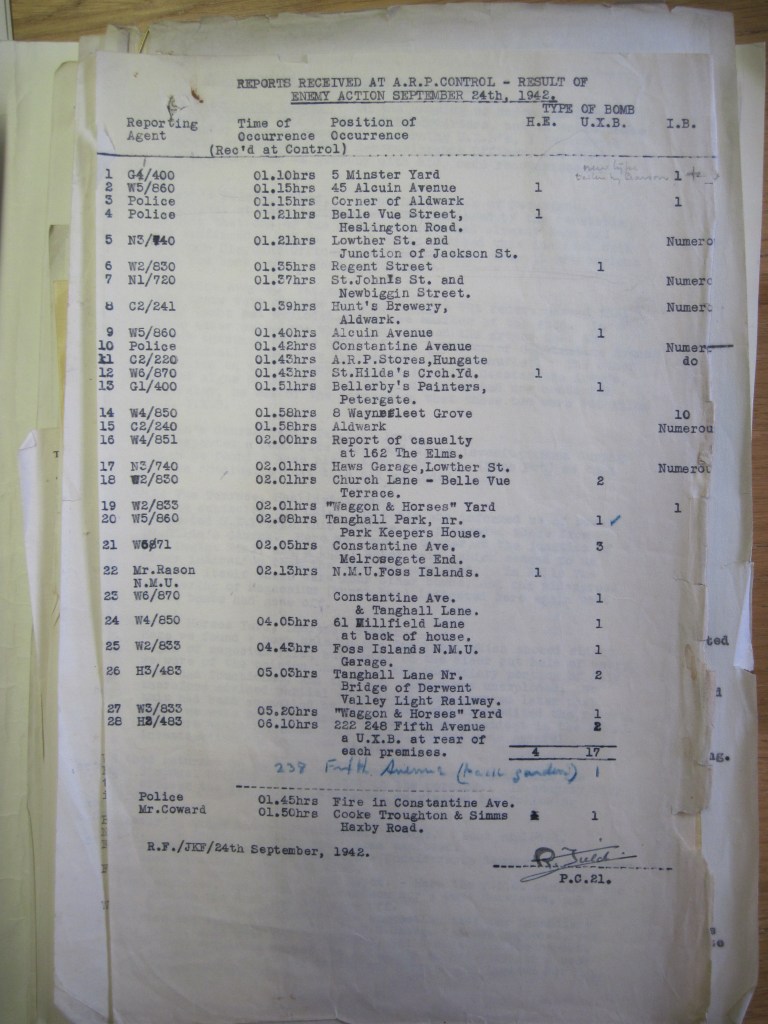

It was against this backdrop of the wider WW2 theatre that on 24th September 1942, at 1:03am, on a clear night with brilliant moonlight, three enemy aircraft were spotted crossing the east coast at Flamborough. Here they dropped flares. Two of the aircraft immediately turned-back across the North Sea. The remaining bomber, a Dornier Do.217, flew on across the county at an altitude of 2,000m (6,000ft) to attack York from the north-east.

The briefest of summaries of the attack would read as the bomber made a loop over the city, dropping its bombs, left to the north east, before turning to make its escape to the south of Bridlington at 1:24. But such a curt summary does not do justice to the confusion in York caused by this raider that night.

The bomber dropped a total of 19 high explosive bombs and two ABB 500 cluster containers, with 120 incendiaries apiece, and flares.

The first reports of the attack upon the city came at 1:08 when two flares fell – one in a field at the end of Woodlands Grove next to the junction with Westfield Grove, and one in a potato patch next to No.48 Wheatlands Grove. Both were quickly put out with a bucket of water.

Shortly after, the two ABB 500 containers were released, scattering 240 incendiary bombs over a wide area of The Groves. Different types of incendiary were used: a steel nosed bomb, an explosive type (with a small charge), and the ‘ordinary 1kg Type’ . St John’s Street was particularly afflicted by the use of the 1kg bombs according to an official report of ‘Air Raid Damage’ of the attack on York. ‘[A]lmost every other house have an incident’, and ‘in many cases some houses received two bombs and in one case three bombs, and another four’. All incendiaries were successfully dealt with by A.R.P. Wardens and Fireguards. The adjoining road, Newbiggin Street, was less fortunate, with ‘[s]everal houses damaged by fire’. Other nearby sites affected included the County Hospital and its grounds, and St. Maurice’s Church – which had also suffered in the sixth raid on York; but all dealt with in time.

In Aldwark, just within the city walls, eight incendiaries fell on and around the Fire Guard Depot at No.26 Aldwark – all predictably dealt with by the staff there. But Hunt’s Brewery in Aldwark received 25 incendiaries and the garage caught fire.

As other incendiaries fell nearby, at No.32 Aldwark, one of the night’s two casualties occurred. An elderly man was said to have ‘died from shock … after the upper room of his house had caught fire’ – and described elsewhere in reports as ‘heart failure’. Elsewhere, bombs fell and were extinguished in Goodramgate, Bedern, St. Andrewgate, and St. Saviourgate. The Blue Coat School in St Anthony’s Hall on Peaseholme Green was affected by three incendiary bombs, but ‘were effectively extinguished by the Master and the senior boys’. In Hungate, which had previously suffered in the fifth raid on York, the prime casualty of the tenth raid was, ironically, the A.R.P. stores, which caught fire after being hit by 12 incendiary bombs and the building burnt out. The fire was likely to have been intense, as the Observer Corps first thought it was a plane that had crashed (possibly an AVRO Anson?)

What was at the time read as a the first high explosive bomb of the raid fell at Alcuin Avenue at 1:15, with ‘casualties trapped in the wreckage’. Five minutes later fire-watchers on the roof of the Mansion House reported ‘report machine-gunning over [the] Minster’. The next two incidents, at 1:25 and 1:27 respectively, capture the varied nature of the attack and two of the main areas affected: a high explosive reported as exploding at Belle Vue Street and then incendiaries on Lowther Street near the junction with Jackson Street. Within the following half hour there were lots of incendiaries reported in the Tang Hall area, at St Hilda’s Church, Constantine Avenue, and ten incendiaries alone at Waynefleet Grove just to the south of the area. Sadly there were casualties in the Tang Hall area. Two men collapsed – Mr. Hill, ‘who had rendered good service by helping the evacuated people’, as noted in a local A.R.P. report, and Mr. Beckwith of No.80 Burlington Avenue, who was pronounced dead due to heart failure. Nearby, in “Post H.7” on Hempland Lane, there was another person who collapsed: part-time Warden J. Kirby.

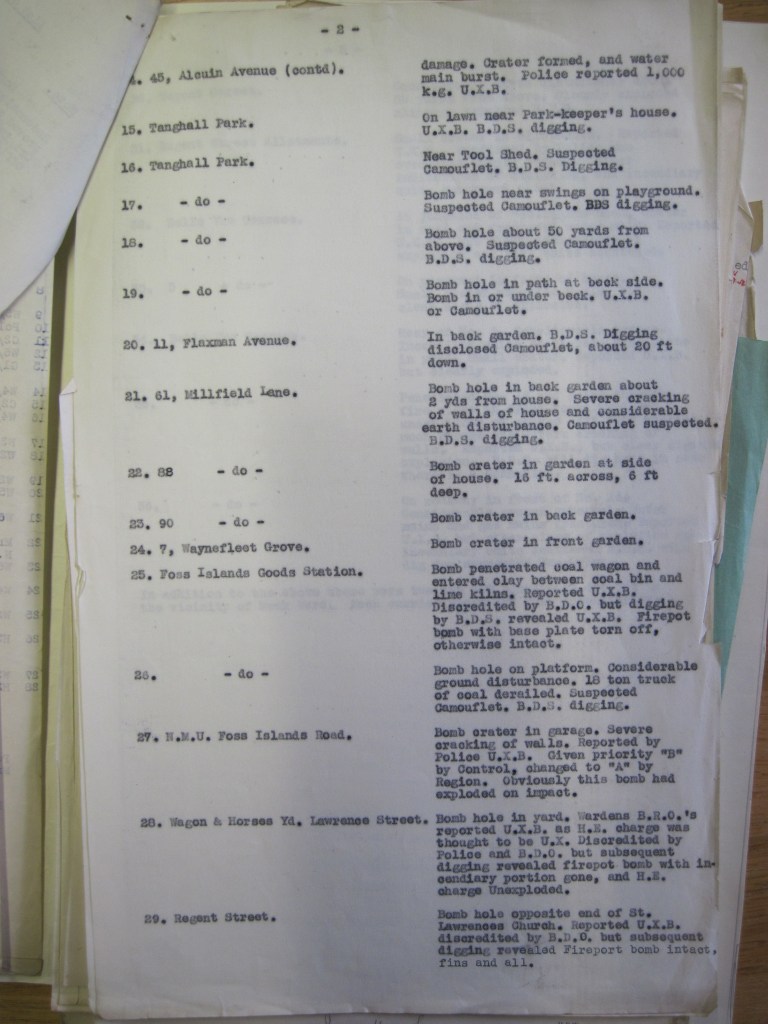

Unexploded bombs were also reported near the bus station on Regent Street, Heslington Road, and behind Bellerby’s Painters Yard on Grape Lane at the back of Petergate. Before the night was through, further six unexploded bombs (UXBs) were reported at Tang Hall Park, including near the Park-keeper’s house.

‘Small fires were started, but damage was negligible’ was the overall verdict of the raid made in an Intelligence Report of the 10th Anti-Aircraft Division. Where these bombs exploded, however, the damage was noted as ‘considerable’: such as at Bellerby’s, Grape Lane; the Northern Motor Utilities depot on Foss Islands; Foss Islands Goods Station Platform, where an 18 ton truck of coal was also derailed; No.12 Belle Vue Terrace (‘[Bomb] penetrated No.12 going through fireplace in front room, exploded under floor of garage next door causing much damage and severe cracking of walls’), or No.83 Constantine Avenue (‘Direct hit on house. Bomb exploded inside causing complete destruction by fire’).

The Intelligence Report also noted how most of the high explosive bombs that fell did not explode. The ‘Result Of Enemy Action’ Report by the A.R.P. confirms this. All but four – later revised to five – of the 19 high explosive bombs that fell came to be categorised as UXBs. All but one of the bombs that exploded were recorded at A.R.P. control within 30 minutes of the raid, but the majority of UXBs were reported long afterwards, the last of them – two bombs to the rear of Nos.222 and 248 Fifth Avenue in Tang Hall – being reported five hours after the attack. Considering this raid was the work of a single enemy aircraft, the considerable disturbance and confusion it caused was perhaps the most of any individual plane on York during WW2.

The A.R.P. report of UXBs indicate that whilst mercifully they had not exploded, they were not without cause for concern to the civil defences services. They of course ran the risk of delayed explosion – or accidental detonation during attempts to defuse them. They also took up considerable resources: requiring evacuation within the vicinity and calling in the bomb disposal squad from Leeds. Due to the number of UXBs in this raid, Bomb Reconnaissance Officer (and Chief Warden for York), R.S. Oloman, had to call in the assistance of his colleague Harold Richardson, the Bomb Reconnaissance Officer and Ward Head Warden for Acomb.

Nor was an UXB always easy to find, or to then identify. Crashing into the ground at hundreds or miles per hour, these weighty bombs were often partially or fully embedded in the ground. In the case of this raid on York, the bombs were thought to include several Camouflets munitions – bombs designed to penetrate deep underground in order to destroy underground structures or create cavities that above structures would then collapse into. One of these, at No.125 Constantine Avenue, was embedded 25ft (7.5m) below the surface.

UXBs would also send debris flying on impact – not too dissimilar to a smaller bomb when detonating. Oloman acknowledges as much in his report when called to a assess a suspected UXB at Bellerby’s on Grape Lane. On arrival, Oloman and Richardson ‘were informed by the constable on duty that one off the Police B[omb] R[econnaissance] O[fficers] had already been and had confirmed a UXB’ Oloman disagreed, reporting, ‘it was obvious that the bomb had in fact exploded’. These two senior A.R.P Wardens had further disagreement with the police when it came to two bombs on the Derwent Valley Light Railway line behind Constance Avenue in Tang Hall. This time, the A.R.P. officials considered these to have exploded, Police Sgt. Paley thought otherwise – suspecting them to be 500kg UXBs.

Most of these disagreements are left unadjudicated. It is unclear who was right – bomb disposal officers or A.R.P. Bomb Reconnaissance Officers. Not ignoring the bias in who was writing this A.R.P. report, there was clearly tensions and some one-upmanship at play in York during this raid, perhaps heightened by the high-stakes responsibility of asking non-combatants to make a hugely important decisions on whether a bomb had exploded or not.

The main reason for the arguments occurring and the broader picture of confusion, is due to this raid witnessing a new type of German bomb being used in York, despite this being the tenth raid on the city and two years since the first raid.

Reporting as Warden for H.3 Post [near Tang Hall Hotel], G. A. Tute described these bombs as making ‘holes 12″ in diameter [0.3m], and about 4′ 0″ [1.2m] in depth. Smoke was still issuing from the holes and splashes of grey-white were found in a radius of approximately 12’0″ [3.6m].’ Tute concluded that they suspected these bombs to be ‘the new type Phosphorous bomb’.

A subsequent report listing 36 bombs dropped during the raid on York accounted them as being the Sprengbrend C.50 type bomb – a combined 50kg incendiary and high explosive bomb. The report details the misidentification of bombs in York from this raid, ranging from landmines, 500-1,000kg high explosive bombs, to Camouflets. It readily explains the confusion that Oloman and Richardson and the police had in classifying the munitions they found. It was not until the afternoon of the raid that all UXBs were confirmed as the Sprengbrend variety and evacuated people allowed to return to their homes and shops. Not that the work of the Bomb Disposal Squad and A.R.P. was complete by then. It was not until 13th October that the last Clearance Certificates were signed off to mark the completion of the bomb clearance operation.

A.R.P Warden Tute complained that when he ‘called to the Rest Centre’ nearby in Tang Hall – at St Aelred’s School, he ‘found that all was confusion. There appeared to be no one in Control’. He added that it ‘did later work itself out to some sort of order, but not as it should be’. Tute heralded instead the actions, in particular, of a civilian – Mrs. Bainbridge of No.222 Fifth Avenue, who ‘took control [of the Rest Centre] and got things going, and also provided sugar and milk and tea cloth; looked after the whole bunch including the Sick Bays. … Her work was really great’. With a touch of English aptitude for fairness, Tute added in his report a request ‘that the sugar and milk supplied should be refunded to this lady’.

In total, the casualties of the raid numbered two dead and 7 casualties: 4 minor and 3 seriously injured.

The chaos created by a single enemy bomber in this raid is clear. It would be wrong, however, to assume that the city was unprepared and undefended.

The anti-aircraft defenders of the city responded with Heavy Anti-Aircraft firing 28 rounds of 3.7″ anti-aircraft shells from H.1 and H.2 (near Redeness Street School and Tang Hall School, respectively), and a ‘”Z” site’ (Z.H.2) at Tang Hall School who fired a further 35 rounds of semi-armour piercing rockets. The Z sites were a new technology allowed to the Home Guard from spring of 1942. They were a short range anti-aircraft weapon system that fired rockets from ground-based single or multiple launchers.

Z.H.1 based near Redeness Street School was told not to fire in this raid due to ‘news of an [AVRO] Anson having crashed in the vicinity at the same time as flares were being dropped’, so the Intelligence Report mentions. Finally, while the Report dismisses the actions of two of the A.A. battalions in York from firing 46 rounds of Light Machine Guns – ‘being of the erroneous opinion that the target was in range’ – it notes contact was made by the enemy aircraft and the defence team on the ground. ‘Z.H.1. report[ed] bursts of cannon fire having been fired on their site and produced in evidence the fuse cap of a cannon shell and several holes in the ground’.

Thanks to Wing-Commander Newbould for making his extensive archive material available to the Raids Over York project team which has been invaluable in producing this account of the raid.