By 17th December 1942, Britain had been at war for over three years. Just over a week later it would be the fourth Christmas under war conditions.

There would prove to be only a couple more ‘War Christmases’ before Victory in Europe happened on 8th May 1945, with the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Indeed, for many historians, the tide of the war by mid-December 17th 1942 was already turning against Hitler. His campaign to invade Russia had already required the withdrawal of many German bombers from operating in ‘The Blitz’. The encirclement and then destruction of the German 6th Army and Italian 8th Army by Russian forces in the Battle of Stalingrad, which was by this point turning against the Axis forces, would be fatal to their wider military capabilities. The importance of all this was, of course, then unknown, and was not reported openly in the press.

And so, whilst decisive action was taking place in Eastern Europe, thousands of miles back westwards in the city of York, it was just another cold December night with Christmas to look forward to and the usual air raid warnings to fear…

The 11th Raid on York

While the 11th raid on York would prove to the final bombing attack on the city of the war, this was of course not then known. It was only just over half a year since the ‘Baedeker Raid’ (29th April 1942) on the city had claimed 94 lives and damaged nearly a quarter of all York properties. Life in the city had got back to as normal as might be expected under war conditions, but vigilance against another attack was maintained.

York citizens, including its Civil Defence force, had endured ten previous raids since August 1940. Changing tactics used by the Luftwaffe that had caught the city out as if complacent: just when the actions of the enemy were being thought to be predictable, they changed strategy and brought havoc from it. From day attacks, to then night attacks; to the use of high explosive bombs to then incendiary flares, and then the use of both: incendiary flares lighting up targets for high explosive bombing; from attacks from multiple bombers to lone bombers; from attacks higher up in the sky, to low-level bombing – arguably the impact of the raids on the people of York was as much, and if not more, psychologically jarring as it was physically scarring.

A change in tactic of attack underlined the 11th raid on York on the evening of the 17th December 1942. Intelligence Reports of the 5th Anti-Aircraft Group mention that the enemy used a new tactic, just as they had done in the region only three days prior. German bomber planes would follow Allied bombers back from their raids over Occupied Europe and Nazi Germany. The tactic involved low-flying to detect RADAR and interception from defending R.A.F. fighter planes. This tactic made it difficult to identify ‘friendly’ from enemy aircraft. Indeed, on the night of the 17th December, in the north of the Yorkshire region, over the Middlesborough area, anti-aircraft fire brought down a R.A.F. Avro Lancaster bomber returning from a raid over Germany, with it mistaken as enemy aircraft. All personnel on board were tragically killed.

On the evening of the 17th December, 5-6 enemy aircraft used the tactic of following R.A.F. bombers back to England. They made landfall over the East Coast between Hornsea and Bridlington around 21.40 hrs, and three of them penetrated deep within the county before being identified as enemy aircraft. On reaching the English coastline, they split into four groups: one plane flew up to the Yorkshire Moors before then turning and coming within five miles north-east of York, only to turn and fly backout over the coast near Filey; a second plane made its way over Malton and as far as Ampleforth before similarly turning back to the Continent; the third plane was only detected as enemy aircraft ‘a few miles south-east of York’ near Dunnington and when flying westward and at 2,000ft (c.600m). (Two further German bombers made brief landfall over Bridlington and Tunstall, but their raid went unplotted and presumably they returned without causing damage.)

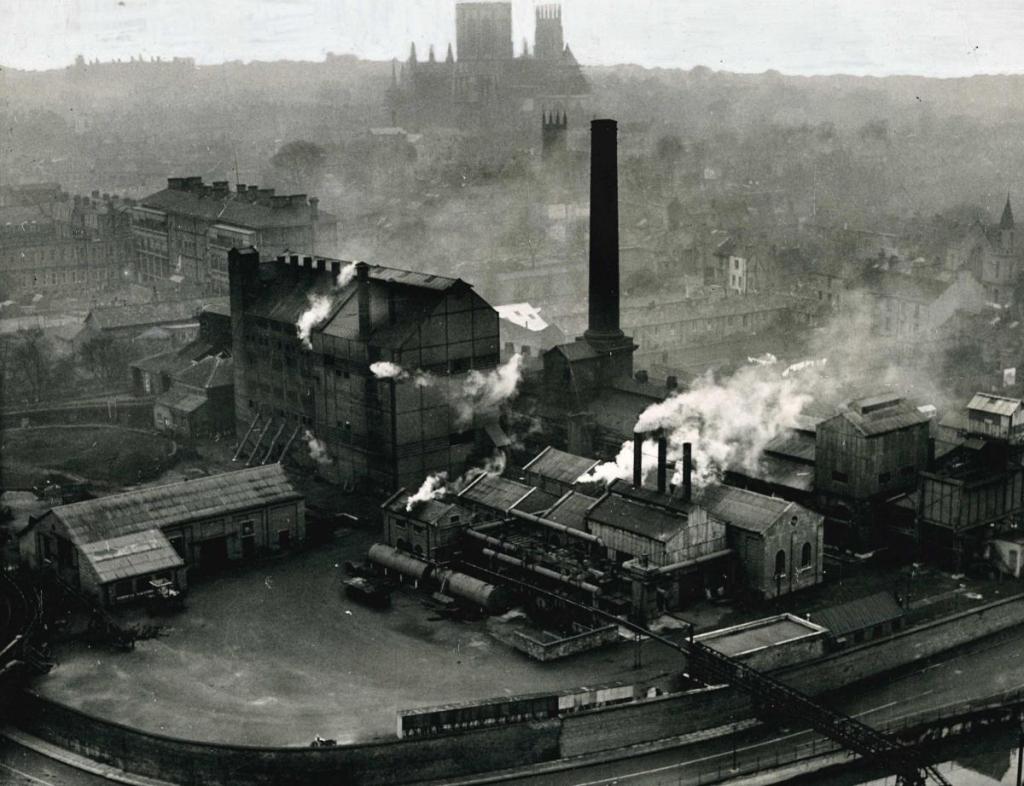

Gaswerks

The enemy aircraft that attacked York did so by diving down to 200ft (61m) before levelling over Layerthorpe and releasing its bombs at 21.56 hrs. It dropped at least one high explosive bomb and several incendiary bombs (totalling 1-2 A.B.B. 500 canisters of 120 individual 1kg incendiary bombs; 4 Fire Pot large incendiary bombs; 2 phosphorous incendiary bombs; and 6 unexploded incendiary bombs).

The high explosive bomb caused damage to the Gas Works in Heworth. Two gas holder tanks were punctured and caught fire. 366,000 cubic ft of gas was lost from Tanks No.4, which had been punctured by over 30 pieces of shrapnel, and 840,000 cubic ft were lost from Tank No.5 after it was punctured more than 60 times, sometimes with shrapnel penetrating right through the tank. A fireman and airmen posted there – possibly supporting firewatchers [see Raid #5 for more details of this role] – were overcome by the fumes and had to be taken to hospital.

Smaller unexploded bombs, each 50kg, were reported to have fallen. One, a phosphorus bomb, crashed into Mr Warrener’s kitchen at No.35 Bilton Street; another in the School Yard entrance on Redeness Street, Layerthorpe, which fell at the entrance of the Warden’s Post (H.1). Unexploded incendiary bombs were also found in Corporation Yard, including a phosphorus bomb found among ‘a pile of sleepers’. A few days later, the Post Warden for H.1, Mr Hemenway, reported several more 50kg unexploded phosphorus or “fire pot” bombs had been found in allotments behind Corporation Yard, Foss Islands. All of these were thought to be Spreng Brand C50 or phosphorous type incendiary bombs. On the 20th December, Warden Hall also commented that whilst looking for other incendiaries in this road, he came across ‘a bomb shaft’ in an embankment near the Derwent Valley Light Railway Station, which was believed to have possibly fallen during the April 28th or September 24th 1942 raid.

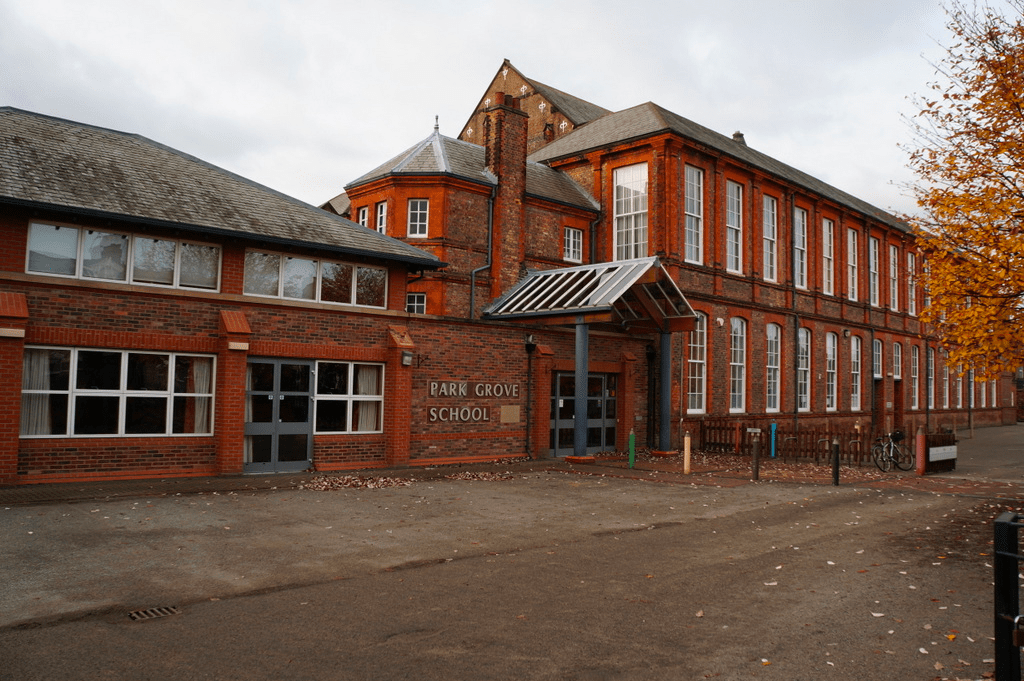

Park Grove School and Heroics

The incendiaries dropped at Park Grove School, Heworth, ’caused extensive fire’. Half of the roof and the first floor of the north-east, Boys’ wing were completely burnt out. It was reported in the press that the damage would have been worse had it not been for the ‘plucky and efficient work of three fire watchers, including two teachers’ – Mr J. Fawcett and Mr W. Coupland (the other firewatcher being Mr S. Anderson). Fawcett and Coupland ‘set about the task of putting out the fires without thought for self and consideration of the risk they ran when dashing in and out of classrooms and darting about the schoolyard, amid the sound of explosions’. The newspaper reported that ‘while Mr Fawcett was tackling one [bomb] blazing in the joinery shop with buckets of water, Mr Coupland scrambled to the top floor and was busy extinguishing an incendiary by means of a fire hose. “All the time the explosive-incendiaries were bursting around us,” Mr Fawcett said, “but we let the hundreds which dropped in the yard burn themselves out while we got to work on all those visible in the school building”.’

14 fires at houses opposite the school were reported in the newspaper, and ‘a church suffered slightly from blast’, but it is not known which church this was.

The newspaper article also praised the ‘excellent work’ performed by the ARP personnel. ‘The fine spirit they showed was reflected in the example of a girl’, states the newspaper – albeit the focus and choice of language now reading as rather patronising and with hints of misogyny – ‘who was blown off her feet by blast, tore her stockings and cut her knees, but went on undeterred to make her contribution in the service’. Four Rest Centres were opened that night, accommodating 85 people.

Scale of damage

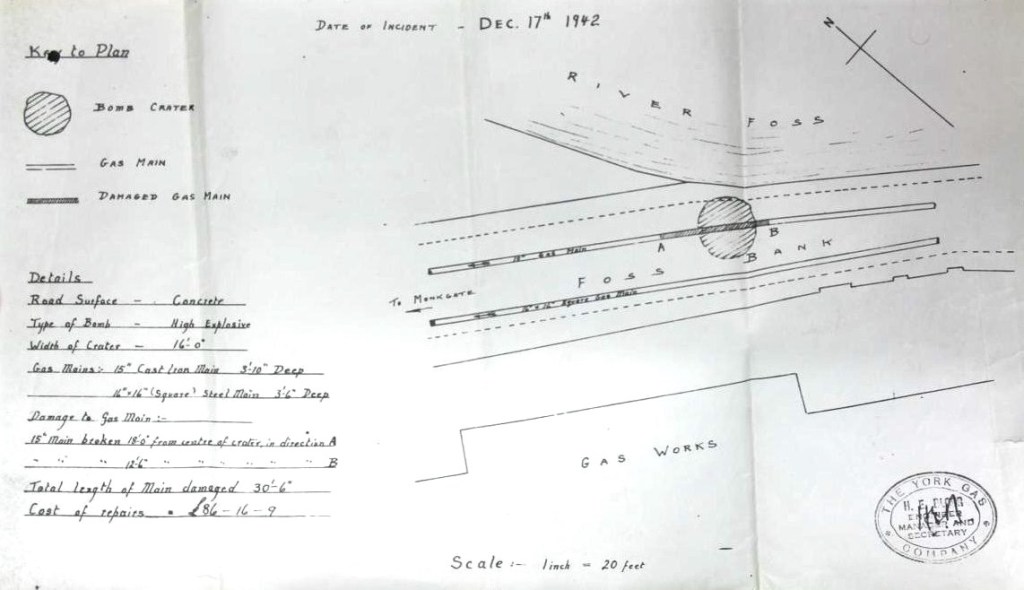

While questioning whether it was a 1,000kg bomb, as initially suspected, that fell near the gas works in Heworth, an investigation into the damage at the gas works documents that the bomb fell approximately 200′ (65m) to the southern side of a large light-steel framework building in the complex. It landed on the Foss Bank roadway, close to the bank of the River Foss, and in doing so damaged the 15″ (40cm) gas mains and 6″ (15cm) water pipe. Blast damage was found across a 500′ (150m) radius.

‘The whole of the side sheeting to the south elevation of the larger building was entirely displaced, having been blown inwards and the sheets considerably distorted’. The asbestos roof was entirely destroyed. It took three days to clear the site to allow the occupant – Monkbridge Constructional Co. – to resume their work.

The damage was not merely to buildings and other structures. There were casualties, too. These numbered 25 people, of which two were fatalities. Frederick Christopher Poole, 34, and Alfred Keech were both killed by bomb ‘splinters’. Four more people were reported as seriously injured and another six invalided. In addition, there were thirteen people reported with slight injuries.

Engaging the enemy

The city’s defences, whilst caught unaware by the danger of the raid until the German bomber was only a few miles away from York, did had success. The No.5 Anti-Aircraft Group and 31st Anti-Aircraft Bridge’s Intelligence Reports detail the path of the plane as it passed over the city. On being recognised as a Dornier Do.217 bomber by Gunner Cox ‘was engaged’ by his Anti-Aircraft Light Machine Gun unit at post H.2. At 21.57hrs, Lt. Ranger, who was located at the post, said their machine gunning was seen ‘to enter the target’. The bomber promptly past the city and over Long Marston turned and headed north over Nun Monkton and away from the city. When it was seen to pass over the Search Light site at Little Ouseburn (CF023), ‘personnel noticed that only one engine was functioning’. It is next thought to have been heard to pass personnel at CK.073 at Tollerton at 22.07 hrs. By the time it reached the Helperby it was thought to be only 200ft (61m) above ground, up in heavy mist, and, while circling near Raskelf, was heard to turn west so as to avoid a hill there. Around 22.15 hrs, the enemy aircraft is likely to be the one that crashed at Crow’s Nest Farm, Easterside Hill, Hawnby, north west of Helmsley.

After first striking a stone wall on top of the hill at an altitude of 1,500′ (450m), the plane was obliterated. Wreckage was strewn over a wide area of several acres. All four of the crew were killed. These were: Oblt Rolf Häussner (pilot); Syrius Erd (observation); Oberfeld-webel Hartwïg Hupe (radio operator) and Oberfeld-webel Ernst Weiderer (Flight Engineer, born 28.12.13).

The Dornier (U5+GR) was part of the 7/KG2 Unit based at Deelen in Holland. Secret files drawn from spying on Nazi reports capture the scale and violence of the destruction of a bomber plane in crashing on a hill, including to the bodies of those onboard. The report states: ‘This aircraft crashed into a hillside and was smashed to pieces. The crew were all killed and it was only with difficulty that two, both Oberfeld-webel, could be identified. Shoulder straps of a Hauptmann and an Unteroffizier were also found’. Weiderer and Hupe were initially buried at Dishforth, but now lie at Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery. Tragically, there were not sufficient remains of Erd or Häussner to be buried (and they are still listed as missing).

Coda

The 17th December 1942 raid on York was the eleventh bombing attack on the city during WW2. The accumulative loss of people in York from the 235 high-explosive bombs and thousands of individual incendiary bombs dropped in these raids totalled 99 civilians with further military personnel killed, the numbers of whom are unknown. An additional 295 civilians were injured in the raids. Even if fortunate enough not to be injured, 2,828 people were left homeless and the owners and tenants of 9,500 homes – about a third of all of York’s 28,000 homes – found their properties damaged.

The eleventh raid on York would prove to be the last on the city. No one knew this at the time, of course. The “Baedeker Raid” on York (29th April 1942) was statistically the ‘main’ or ‘big’ raid on the city, and certainly felt so when it occurred.

While the scale of bombing raids on British towns and cities were greatly reduced after the Baedeker Raids of April 1942 due to Nazi Germany’s concentration of its bombers on its Eastern Front, with time, Germany would launch its vengeance attacks through the use of V-1 (known as a “doodelbug”) and then V-2 rockets. The near randomness of these huge, deadly bombs crashing down on British soil and city went to perpetuate British civilian fears, and irrespective of the weapons actual operational range limitations. Citizens in York would have been just as terrified of these rocket attacks as any other subject in Britain.

The scale of damage and casualties suffered in the Nazi air raids on York should, however, be put into context of the wider war, both nationally and internationally.

The physical damage of York does not compare with that of bigger cities – of Hull, Liverpool, Sheffield, and, of course, London. Nor does it compare to the scale of destruction wrought by Allied bombing in Occupied Europe and Nazi Germany, and microscopic compared to the use of hydrogen bombs in Japan in 1945.

13–15 February 1945. IMAGE: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1994-041-07 / Unknown author / CC-BY-SA 3.0

By a quirk of historical timing, another event on the 17th December 1942, aside from the eleventh and final raid on York, helps add perspective of the scale of loss, fear and immorality from inhumane action during the war.

The human tragedy of the Nazi regime and the WW2 conflict that helped facilitate it has come to be understood through the horror of the Holocaust. On the 17th December 1942, the newly-formed United Nations brought that word – Holocaust – into public awareness. The Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations on the 17th December was the first formal statement to the world about the mass-executions of Jewish people in Occupied Europe.

Issued jointly by American and British Governments, in the House of Commons, the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, pronounced that the Declaration condemned “in the strongest possible terms this bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination” and made a “solemn resolution to ensure that those responsible for these crimes shall not escape retribution”. The Times reported, ‘Moved by the horror of Mr. Eden’s recital of German atrocities against the Jews, and by the stern protest and warning of retribution which he uttered in the name of the British and allied Governments, the House, prompted by a suggestion from a Labour member, rose spontaneously and remained standing for a minute’; a profound gesture usually reserved for the death of a monarch.

Thanks to Wing-Commander Newbould for making his extensive archive material available to the Raids Over York project team which has been invaluable in producing this account of the raid.