Sunday 2nd August 1942 was 95 days since the ‘Baedeker Raid’ (29th April 1942) in York, which had brought sizeable destruction and loss of life to the city. It could be forgiven for assuming that peace and quiet had once more returned to this provincial city by August. The reality was that WW2 continued, unperturbed and life did not swiftly go back to how it had been prior to the Baedeker Raid.

As late as 7th June, unexploded bombs were still being dealt with in York by 14 Bomb Disposal Company, the final one being at the LNER carriage works on Poppleton Road in Holgate. The challenging nature of this task is shown by the subterranean depths from where these bombs had to be recovered – from 10 – 27 feet (3 – 8.23m) in the ground – approximately from the height of a shipping container to that of a traditional two-storey home with a pitched roof; quiet some digging, let alone the risk and skilled work required.

After the Baedeker Raid, the military and civilian authorities launched a publicity campaign to reassure local citizens that York’s damage and loss had been worth it as part of the war effort. A week after the raid, a 15-minute demonstration of captured enemy aircraft – ‘The Captured Enemy Aircraft Flight’ – was held at RAF Clifton, as part of the ‘Enemy Aircraft Flight RAF’ – nicknamed the “Rafwaffe”.

Defence of the city, too, was strengthened. By the 9th May 192, a night ‘decoy’ aerodrome was opened near Bugthorpe in East Yorkshire – about 11 miles east of York – to better protect RAF Clifton, which had been targeted in the Baedeker Raid.

In the same month, temporary ‘Starfish’ decoys were established 500m to the east of Bland’s Plantation in Fulford, then an outlying satellite village of the city. They acted as decoys for the actual Luftwaffe targets – in this case, York – and used burning oil to act as if the city was on flames, drawing the bombers to attic them rather than the city to the north. (Today, Fulford’s Starfish decoy is a scheduled monument).

A Light Anti-Aircraft troop was deployed to York from the 26th May, and positioned their guns at the following locations:

- Odeon Cinema;

- Station Hotel;

- LNER Offices;

- Terry’s Factory;

- Bootham Bar;

- Dean’s Corner;

- Monk Bar, and

- Clifford’s Tower.

Together, these sensible defence measures were no doubt welcomed by the authorities to help convince citizens that they were better defended, and therefore the likelihood of another raid of a scale of the Baedeker Raid, or worse, was less likely.

All the same, the devastation of the Baedeker Raid on York was starkly cast back into the minds on the 29th July 1942 with the delayed release of the official report of the raid for public consumption.

The ninth raid on York arrived on Sunday 2nd August 1942 at 4.36pm. There had only been one air-raid warning in the city since the Baedeker Raid. But this was to be a very different sort of raid than the city had endured, at least since the first raids in 1940. Thus raid occurred in daylight – likely to account for the relatively large volume of casualties – mostly people enjoying their summer Sunday afternoon. It was also seemingly a single raiding aircraft attacking the city, and was conducted at speed and low altitude.

At 3pm, a Dornier Do-217 bomber left Soesterburg in Occupied Netherlands and made landfall on the Yorkshire coast twelve miles north of Hornsea. The Dornier was one of several in a unit from II/KG40 who came across the North Sea and dispersed to conduct raids in Lincolnshire, East Anglia, and, in this case, York.

Using the cover of low-lying cloud and heavy rain – ‘ideal weather for cloud hopping’ as the Intelligence Summary by the 10th Anti-Aircraft Division later referred to it – the German Dornier bomber was misidentified as a British training aircraft by the air defence. Consequently, it plotted its course to York via Driffield at 2,000ft undisturbed until finally being suspected as a hostile aircraft at 4.28pm, only minutes before attacking York.

The aircraft was spotted flying low over a golf course on the outskirts of the city. It approached York from the east, swung to the south of the city, before returning to head eastwards and descended to 500ft when approaching the city centre.

At 4.36pm – four minutes before the air-raid siren was sounded over York – the Dornier Dornier dropped four, 500kg high-explosive bombs, causing damage to over 400 buildings.

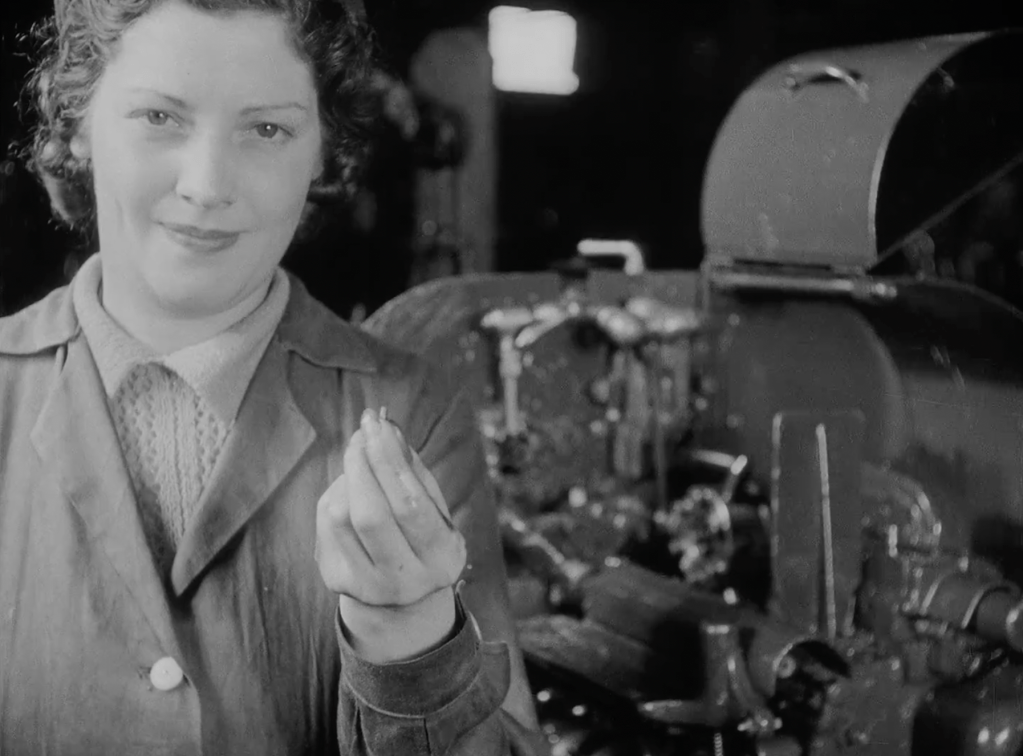

According to the Ministry of Home Security’s ‘Bomb Census’ records, the first bomb fell on Cooke, Troughton & Simms’ Buckingham Works in Buckingham St, which, according to the Civil Defence report, was being used to store hospital supplies. (Cooke, Troughton & Simms’ were certainly part of the military war effort, employing 3,300 people in York during the war to manufacture theodolites which were used in artillery observation, although this work was most likely conducted at their larger Haxby Road factory.) Fortunately, this bomb failed to explode, causing no casualties, and was subsequently rendered safe by 28 Bomb Disposal Sector during August.

The next bomb fell on a slipway 20ft from the River Ouse, near 26 Skeldergate, approximately 700ft northwest of Skeldergate Bridge. Hitting the parapet wall of the slipway, it sent shattered brick and stone flying all around. A lean-to timber roof was destroyed nearby, but the extent of the blast was far wider. A report on the damage considered the blast damage of this bomb to have been ‘abnormal’, with damage extending to Micklegate, Coney Street and High Ousegate.

A National Fire Service [NFS] fireman, Sidney or Stanley Thompson, who was 33-years old, was killed on a National Fire Service River Patrol boat at King’s Staith. Six others – two men and seven women – were seriously injured and a further 13 men, 13 women and 10 children suffered minor injuries. Of all the bombs that fell on York during WW2, this is thought to have caused the most casualties.

Given the speed of the attack, it is likely that fatality of a fireman on a National Fire Service River Patrol boat was a coincidence, rather than an attempt by fire service to tackle the bombs. York’s main fire station was then on Peckitt Street, which runs down to the River Ouse. The National Fire Service River Patrol boat was likely moored or in use nearby – sadly too close to the explosion, killing the fireman and injuring many other people.

The next bomb fell at the foot of the steps to Cliffords Tower but failed to explode. It was subsequently rendered safe by 28 Bomb Disposal Sector during August.

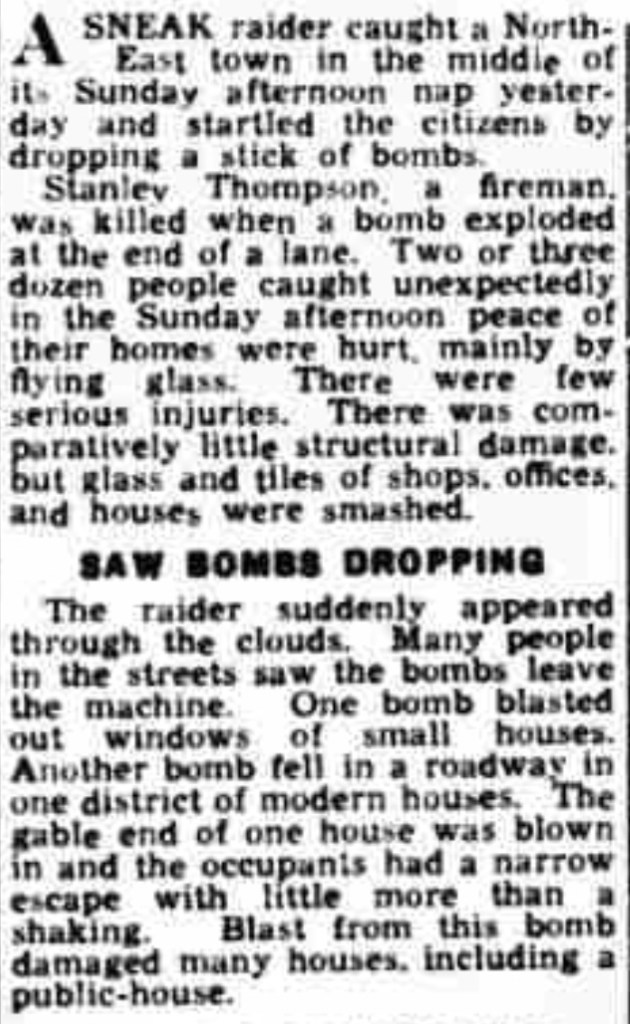

The final bomb fell 40ft from the gable end of a house on the Albert St, just off Walmgate. It landed on the concrete surface and caused damage to numerous houses in Albert St and Hope St. Six people – a man and five women – were left with minor injuries. Amongst the damage to local properties, according to the report in the Yorkshire Observer, a gable end of a nearby house was left caved in, and ‘[b]last from this bomb damaged many houses, including a public-house’ – most likely to have been the Brown Cow on Hope Street.

As quickly as the raid began, so the it ended. The Dornier fled, climbing to 6,000ft, using cloud cover to move east, crossing the coast at Hornsea at 4.50pm before heading out to sea. Two Bristol Beaufighters of 406 Squadron from RAF Scorton were sent out to patrol, but neither made contact with the Dornier, which arrived back to base safely.

The target of the raid is unclear. None of the locations that were hit by bombs were part of the Luftwaffe’s assessed targets for the city. The direction of flight path of the bomber – heading around the southern side of the city to line up a bombing raid from west to east, suggests that the station’s railways and capacity was the intended target, but the bomber, perhaps flying far lower than in previous raids, looks to have overshot its target and the bombs instead came crashing down in Bishophill, the Castle Grounds, and Walmgate areas. But this remains only speculation.

As touched upon above, this was an unusual raid on York compared to the earlier ones it had experienced. Recent raids, including the Baedeker Raid in April, had involved a number of aircraft working in partnership to identify targets, highlight them to fellow bombers through the use of flares or incendiary bombs, then drop high-explosives on the targets. A single bomber in this raid was just that – working alone – and had limited opportunities to make other than a single flyover York in its raid.

‘Tip and Run’

This new pattern of raids on York can be seen in light of a new direction in the Luftwaffe’s attacks on Britain at the time. Their new tactic was called ‘tip-and-run’ (or ‘hit-and-run’) raids.

The introduction of faster fighter bombers in early 1942 – in particular the Focke Wolf FW-190 – allowed the Luftwaffe to use airbases in occupied countries such as France and Netherlands to do fast raids over parts of Britain.

Using very low-level altitude flying – as low as 5 meters above the ground – to avoid Radar, and high-speeds of around 450kph, these fighter-bombers appeared seemingly from nowhere, attacked their targets at speed, before turning back to base. They would keep low before rising to 500m on approach to their target, then levelling off when 1,800m away, and finally dive at an angle of 3°, reaching speeds of 550kph, before pulling up and dropping their bomb(s).

The Luftwaffe first trialed this ‘tip-and-run’ tactic on Britain on Christmas Day 1941, attacking a target in Sussex. January 1942 saw 44 further attacks across Kent, Sussex, Dorset, Hampshire, Isle of Wight and particularly on Cornwall. From March 1942 onwards, these new-style raids intensified, and further still from mid-July when the aerial superiority of the Focke Wolf over the Spitfire was demonstrated.

The ‘tip-and-run’ raids led to greater effectiveness and lower loss of German planes than in previous raids. For the British military, it resulted in weakened effectiveness in combatting the Luftwaffe, shooting less places down, as well being less able to protect British military and civilian targets.

For British civilians, the new ‘tip-and-run’ raids challenged the new-normality during wartime of responding to night-time air-raid sirens, often raised when bombers were spotted crossing the British coastline – which in the case of York gave a 10-15 minutes warning before they were over the city, ample time to head to the relatively safety of public or private bomb shelters. Now, seemingly German bombers could appear overheard and attack with impunity, and at anytime, day or night. The fear of those out enjoying a summer Sunday afternoon on King’s Staith on the 2nd August, only to see a low-flying Dornier at speed, dropping its bombs on the city, must have been palpable.

Until August 1942, the ‘tip and run’ attacks by fighter-bombers were limited to the English southern coastline, including shipping. Hereafter, attacks were made further inland. This included the Baedeker Raid on Canterbury on the evening of 31st October 1942 – the largest daylight attack by the Luftwaffe on Britain since 1940.

While the use of fighter-bombers never extended to attacks further north than the English southern or East-Anglian coastlines, the 2nd August 1942 raid on York used a similar tactic. The Yorkshire Observer, which wrote about the raid the next day – albeit referring to York anonymously as a ‘North-East inland town’ for defence the realm purposes – considered the attack part of the wider ‘tip-and-run’ attacks.

One of the differences, however, was that a Dornier bomber was much slower and less manoeuvrable compared to a fast fighter-bomber such as the Focke Wolf FW-190. It was able to emulate the ‘tip-and-run’ tactic, but offered none of the aeronautical prowess of a fighter-bomber to battle its way out of a dogfight if the RAF made contact with it. It was a high-risk strategy for the Dornier crew attacking York on the 2nd August. This might account for their pragmatic reasoning of circulating low around the city – as much to line up a direct escape route back to the North Sea as the bombing run – as well as seemingly missing its target when operating far closer to the ground when bombing than in earlier raids.

Thanks to Wing-Commander Newbould for making available his detailed archive research to the Raids Over York project team.

The history of the ‘tip-and-run’ raids on Britain during WW2 can be found at this weaponsandwarfare.com webpage.